Arabic as a language for artistic expression has recently been enjoying a resurgence of interest as a result of the social and political uprisings that have been occurring across the Arab world. Interestingly, however, this resurgence is not only limited to the Arab world, but is also occurring in what many would consider rather unlikely territory: Israel – a country where Arabic was, and is still by many considered as the language of the ‘enemy’.

For many singers and musicians living in Israel today, Arabic is a source of inspiration as well as a link to their roots. Neta Elkayam, an Israeli singer of Moroccan origin explained how singing in Arabic enables her to pay tribute to the Arab Jews who left everything behind them to come to Israel many years ago. ‘Hebrew [received] a lot of interest and erased many other languages that Jews had brought with them in the last 60 years’, she told me, further adding that ‘Many of the Moroccan Jewish musicians came to Israel, sung in Arabic, and died in unfortunate oversight, just because they performed in Arabic with their own style’. Her ‘answer’ to this predicament? ‘The least tribute we could give them is to take [forth] their legacy, the way they wanted it to be’. Neta is not an exception; rather, she is part of a larger artistic Israeli scene composed of highly talented musicians and singers who find in the vast repertoire of Arabic music an answer to the many questions they have about their identities. Hailing from countries such as Morocco, Yemen, Algeria, Libya, Iraq, Yemen, and Egypt, they creatively bring together the remnants of their ancestors’ cultures to produce new musical genres.

The ‘architects’ of Israel – i.e., those who came in waves at the end of the 19th century to fulfil their dream of creating a state – decided that only Judaeo-European (Ashkenaziin particular) culture was worthy of serving as a basis for that of the new state. North African and Middle Eastern Jewish populations (referred to as ‘Mizrahim’) who emigrated to the ‘Promised Land’, either because they no longer felt at home in their own countries, or because they felt religiously obliged to play a role in the formation of the Israeli state found themselves rejected by the dominant Ashkenazi elite. As Edwin Serroussi and Motti Regev noted in their book, Popular Music and National Culture in Israel, the Ashkenazi society of the time ‘evolved around two major, interrelated themes: the rejection of the culture of the Jewish Diaspora … and the invention of a “new” Jew, the Hebrew person, the Israeli’. The ‘new’ Jew could have been anyone but a person of Arab or Middle Eastern origin.

Accordingly, the Ashkenazi ‘architects’, who believed that Israel’s primary concern would be to define and build a new national identity rejected any form of cultural participation on the part of the Mizrahim; in fact, in them they even saw a threat to their ambitions, and as a result did everything in their power to ‘civilise’ and ‘integrate’ them into the new society, particularly focusing on erasing their idiosyncrasies to maintain cultural hegemony. As ‘Oriental’ culture was largely perceived as inferior and primitive by the elite, discrimination against the Mizrahim was rife. Arye Gelblum – a prominent Israeli journalist – saw in the waves of North African immigration a danger to Israel’s existence, which he clearly expressed in the April 22 1949 edition of Haaretz, a leading Israeli newspaper:

A serious and threatening question is posed by the immigration from North Africa. This is the immigration of a race we have not yet known in the country. We are dealing with people whose primitivism is at a peak, whose level of knowledge is one of virtually absolute ignorance, and, worse, who have little talent for understanding anything intellectual … the Kibbutzim will not hear of their integration … They will ‘absorb’ us, and not we them. The special tragedy of this absorption is that there is no hope, even with regard to their children.

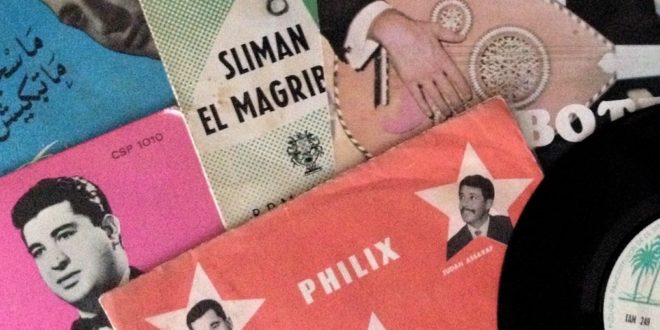

As Jews from North African and Mediterranean countries were put together in maabaras – refugee camps that were established to absorb the large immigrant influxes in Israel – music began to play an important role in the formation of the new Mizrahi culture. Weddings and other festivities, however, were the only outlets available to the Mizrahim, as official radio stations and mainstream record labels rejected the voices of the emerging Mizrahi scene. Fortunately, clubs and wedding halls did not hesitate to promote the Mizrahim, giving them stages not afforded elsewhere. As well, the invention of Philips cassettes in the early 70s revolutionised official music distribution channels, contributed to the emergence of Mizrahi talents, and resulted in the mass production and distribution of tapes by local singers who, most probably, wouldn’t have otherwise found fame. However, terms such as ‘bus station music’ (a reference to the Tel Aviv bus station that was transformed into a marketplace for Mizrahi cassettes) and musica cassetot (lit. ‘cassette music’) are still used to denigrate and label as culturally inferior Mizrahi music.

Musicians such as Zohar Argov, Avihu Medina, Jo Amar, Haim Moshe, and Ahuva Ozeri ushered in the beginning of a new era of Mizrahi ‘stars’ who found in the invention of the cassette a powerful tool to make their voices and cultures heard. Cassettes played a large role in negotiating, what Amy Horowitz calls in her book, Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic ‘disputed cultural territories’, and striving for cultural legitimacy and recognition in Israel. Today – although the socioeconomic conditions of the Mizrahim and the disparities between them and the Ashkenazim aren’t much better, one may argue – it is more common today to come across Oriental rhythms on Israeli mainstream radio stations, and less surprising to hear Arabic songs performed by Israeli Jews.

“… The young generation of Mizrahim has the feeling that there is still much work to be done in order to receive due recognition for their culture and heritage in Israel”

As Amit Haï Cohen, an Israeli musician of Moroccan and Tunisian origin (who also plays with Neta Elkayam) told me over a cup of mint tea during a visit I made to Jerusalem earlier this year, ‘Mizrahi music, to become mainstream, had to use a bottom-up approach. The Mizrahi music came from the people’. The popularity of other genres, however, was largely made possible courtesy state media. Zohar, another Israeli friend of Moroccan and Iraqi origin sees the rising popularity of Mizrahi music as a natural result of a shift in demographics, as the Mizrahim constitute a much larger percentage of the population today than they did previously. ‘[Mizrahi music] can be seen as mainstream in the “second” Israel, the Mizrahi Israel … This is a very large portion of the country, so [Mizrahi music] can be seen as mainstream on the whole as well’. Ophir Toubul – a co-founder of Café Gibraltar, a think tank for Mizrahi music and culture – on the other hand, made sure I understood that no ‘rebirth’ is occurring, as ‘people here always used to sing in Arabic’. However, he is also of the opinion that the young Mizrahi generation sees in the growing visibility of this specific repertoire a political statement and a ‘[continual] search [for] authentic identity’.

This ‘search’, as Toubul puts it, has led many Israelis to label themselves ‘Arab Jews’, even though Hebrew is their mother tongue. Reuven Snir, a professor of Arabic literature at Haifa University explains how this identity issue is a result of a contemporary political context of marginalisation: ‘Everyone who studies the identity of those intellectuals who have recently been adopting the Arab-Jewish identity – we may call them the “Neo-Arab-Jews”, he says, ‘can observe that idea of creation, sometimes a creation ex nihilo – out of nothing – at least with regard to the most important component of that identity: the Arabic language’. He also makes mention of the fact that ‘the major current activists of Arab-Jewish identity are not fluent in standard Arabic’. The expression of this identity, through singing – especially in Arabic – has become for these ‘Neo-Arab-Jews’ what Snir calls ‘part of the politics of resentment’.

Today, the bulk of this identity ‘struggle’ is being carried out on the Internet. Social media is to Neo-Arab-Jews what Philips cassettes were to the first Mizrahi Jews in Israel – a major tool in spreading awareness about their cultural heritage. Many Facebook pages, YouTube channels, websites, blogs, and forums are being created to share Mizrahi music and connect people from not only around Israel, but also the Arab world and the world at large. David Regev Zaarour, an Iraqi-Israeli musician (grandson of the renowned Youssef Zaarour) recently decided to pay tribute to his family by uploading on YouTube all of his grandfather’s recordings. ‘I had to put [the recordings] on YouTube to make [them] memorable. I got reactions and photos from people, especially from Iraq’, he says in a short documentary he created. As well, David also preserves the cultural legacy of his family and his roots by performing Arabic Iraqi and Egyptian music in his band, La Falfoula.

‘In another 20 years, we’ll have a musical style and people will not say: this is Eastern, this is Western’, said Haim Moshe, one of the first Israeli musicians to combine Oriental and Western rhythms, in 1984. ‘In another 20 years, [Mizrahi music] will be known as original, authentic Israeli music’. Even though ethnic diversity and the state of cultural production today in Israel would confirm Moshe’s predictions, the young generation of Mizrahim has the feeling that there is still much work to be done in order to receive due recognition for their culture and heritage in Israel.

_____________________________________________________

(*) This article was originally published on REORIENT. Read the original article. The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily represent ForMENA

ForMENA Council for MENA affairs

ForMENA Council for MENA affairs