By ; Younes Hassar, for International Policy Digest (*)

Whole cities have been destroyed. Massacres and unspeakable atrocities have been visited upon an increasingly weary and desperate population. A growing flow of refugees and displaced persons wander across the roads in search of shelter and salvation. At the same time, vicious and bloodthirsty armed groups roam the country pillaging and ravaging. One’s mind races immediately to Syria and its plight while reading these lines. But this is Germany; this is the heart of Europe at the turn of the 17th century. From 1618 to 1648 for a gruesome 30 years, and as James Clavell so neatly put it in his 1970’s picture The last Valley, the princes and mighty “butchered” Europe in their quest for more power and wealth. The Thirty years war was immensely destructive: historians estimate that some parts of Germany lost up to 50% of their population and that the country didn’t recover until a century later. The war pitted Protestants against Catholics, Habsburg imperialists against princes eager for more autonomy, warlords with their mercenary armies against trading cities. It drew virtually all of the major European powers in a geopolitical tussle the old continent had never experienced before. But more importantly, it gave rise to a new order that would transform international relations and the European state system.

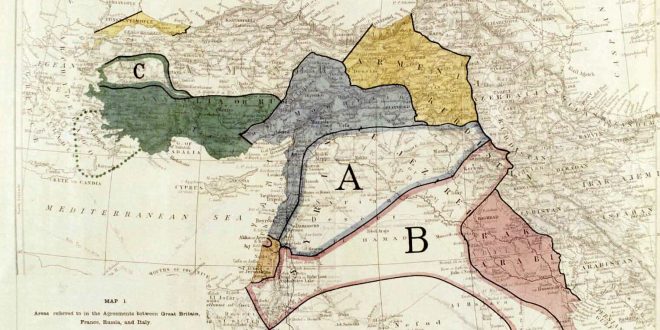

As Syria and the Middle East’s woes don’t seem to have an end in sight, comparisons with Europe’s 17th century tragedy have been regularly popping up. The sectarian flavour of both situations and the involvement of regional powers certainly add fuel to the comparative drive. But very often, the comparison ends up reinforcing a sense of fatality with the impression that the conflict has no solution, that the Middle East is a complete mess and that it needs a total make-over. Moreover, as last month marked the 100th anniversary of the Sykes-Picot agreement, recurring voices have been calling for a total redrawing of the map calling into question the sustainability and the relevance of the current borders.

Truth be told, pundits haven’t waited for the anniversary of the infamous colonial carve-out to advocate new borders for the Middle East. In the summer of 2014, the dramatic advance of the Islamic State and its subsequent smashing of the border between Iraq and Syria prompted commentators to wonder whether a new arrangement could be the solution. The main argument invariably repeated was that the borders were artificial and that they brought together heteroclite and competing ethnicities and sects.

The states created on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire were artificial in essence because they didn’t follow the ethnic and religious fault lines of the Middle East. This idea implies that a political entity grouping various religious and ethnic communities is structurally deficient and is headed to ruin and failure. The violent breakup of Yugoslavia during the 1990s seemed to confirm this line of thinking: the Middle East was next in line and needed new homogeneous political units. Various articles and publications explored the modalities. One of the most prominent analysis was penned by Robin Wright in the New York Times in the fall of 2013. Under the title “Imagining a Remapped Middle East,” the Woodrow Wilson fellow proposes a complete revamping of the region.

According to Mrs Wright, “The map of the modern Middle East…is in tatters,” she tells us that “The centrifugal forces of rival beliefs, tribes and ethnicities—empowered by unintended consequences of the Arab Spring —are also pulling apart a region defined by European colonial powers a century ago and defended by Arab autocrats ever since.” Wright goes on laying out her vision of a fragmented Middle East as a mosaic of states based on sectarian and tribal identities. Of course, she is not alone in arguing for new borders. In a 2008 The Atlantic piece, Jeffrey Goldberg comes to the same conclusion: the Middle East’s current configuration is not sustainable. The entities born out of the Ottoman’s demise have lived. It is time to redraw the map.

It is quite disturbing that yet another time Westerners are busy thinking about drawing lines in the Arab world. The irony of it all is that by attacking the Sykes-Picot legacy they cloak themselves in an anti-imperialist, anti-colonial and liberal posture. But in reality, it is quite revealing that the one absent element from their analysis is the most concerned variable: the people on the ground. As much as Arabs resent the Sykes-Picot agreement and its betrayal of their legitimate national aspiration, they fear much more the further balkanization of their region. The vast majority of Syrians, be it pro-government or rebels, Sunni or Alawite, remain very much attached to the territorial integrity of their country. This makes the border approach quite flawed and its eventual outcome not very conclusive to say the least. Who says that more homogenous states won’t be at each other throats and plunge the region into yet another bloodbath?

So if the “let’s re-organize stuff” approach seems hazardous, is there another path? Well, here comes the Thirty Years War. Beyond the cataclysm and the horror it represented for contemporary folks and immediate chroniclers, the war and most importantly its outcome represent a true defining moment in the history of Europe, if not the World. We have been brought up with history courses that engraved deeply in our psyche events like the Fall of Rome, the spread of Islam or the Renaissance as milestones with long lasting consequences in world history. The Thirty Years War and its settlement have all the reasons to be part of this club. The war is seen by political scientists as some kind of turning point in which concepts like territorial sovereignty and balance of power supplanted old feudal dynamics and the imperial ideal of universal sovereignty.

After 30 years of sectarian strife and foreign interventions, the German princes came to an understanding with the Habsburg emperor in what would be remembered as the Treaty of Westphalia in October 1648. European powers from France and Sweden to Spain and Austria reached a point of exhaustion that forced them to end the conflict and find a compromise. The Treaty of Westphalia (or more accurately treaties as it is composed of two agreements: one reached in Munster and the other in Osnabruck) was thus a peace of exhaustion. Far from being a revolutionary or even a visionary text, the treaty was interested in ensuring the minimum conditions for peace. But it is the underlying or subsequent principles emerging from these minimum conditions that would be the true game changers. The negotiators came quickly to the conclusion that if Europe was to find peace and stability, the warring parties (be it Catholics vs Protestants on the local scene or pro-Habsburg vs anti-Habsburg on the continental one) needed to accept the other. Tolerance or more exactly toleration was the first necessity. The peace of Westphalia consecrated the principle of tolerance by establishing equality between Protestant and Catholic states within the Holy Roman Empire and by providing some safeguards for religious minorities. The idea of Holy War was thus inexorably moving towards irrelevance. Degrading the rallying and mobilizing dimension of sectarian affiliations is surely a must in the case of the present-day Middle East. Decades of sectarian incitement coupled with retreating state presence in the public sphere have led to the crystallization of identities based on beliefs. The destruction of Iraq during the first decade of the new century gave leverage to a growing regional polarization between Shia and Sunni that keeps on feeding itself with the various regional confrontations going on today from Syria to Yemen. But reaching some kind of religious concord won’t be enough.

_________________________________________

(*) This article was originally published on International Policy Digest. Read the original article. The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily represent ForMENA

ForMENA Council for MENA affairs

ForMENA Council for MENA affairs